ARTICLE AD BOX

MaryLou Costa

Technology Reporter

Getty Images

Getty Images

Queensland has seen serious winter and spring flooding

As the skies unleashed six months of rain in February over North Queensland, Australia, many locals endured sleepless nights, unsure what level of flooding and damage they would wake up to.

Perhaps none more so than Andrew Brown - a cybersecurity lecturer by day, with a side hustle as a self-made amateur weather forecaster.

Few know that Mr Brown is the brains behind Wally's Weather - a Facebook page with 107,000 followers and 24 million monthly views, focusing on weather across the tropical state of Queensland.

During the record-breaking flooding, when 400 people were forced to evacuate their homes, Mr Brown published round the clock posts, even waking in the night to share updates, out of a sense of duty and responsibility to his audience.

He even left work early when he spotted on his weather radar that five hours of non-stop rain would be approaching, advising not just his Facebook followers, but his bosses, colleagues, wife and adult children to do the same.

"When there's a big weather event, you try and give people as much notice as possible."

He is based in Townsville, the regional centre of an area known for a rain-drenched, hot, humid wet season from January to March.

"People want to know what's going on, because even if they lose power, they've probably still got an internet connection. These systems are notorious for happening at night time when you can't see what's going on, so you do feel like their eyes and ears," says Mr Brown.

Mr Brown's active, highly engaged Facebook audience is indicative of how more members of the public are turning to social media for news and weather updates - in the US, it's how 20% of adults get this information, according to Pew Research Centre.

People pay as much attention to influencers on Facebook as they do journalists and the mainstream media, and actually pay more attention to them than their mainstream counterparts on YouTube, Instagram and TikTok, according to a study by the Reuters Institute and University of Oxford.

Prof Daniel Angus is director of the Digital Media Research Centre at Queensland University of Technology.

When Brisbane-based Prof Angus found himself caught up in the heavy rain and flooding brought on by Tropical Cyclone Alfred also in February, he preferred to follow official advice from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, as he believes they still provide the most accurate forecasts and warnings.

Prof Angus recognises the rising popularity of weather influencers like Mr Brown's Wally's Weather as stemming from not just a broader trend of public mistrust towards mainstream media and government sources, but about filling gaps in coverage and relatability.

"Weather influencers have gained popularity, particularly in rural and regional areas, because they provide highly localised, real-time updates that mainstream media can often overlook," says Prof Angus.

"They engage directly with their audience, offering personalised analysis and responding to community concerns in a way that traditional news outlets typically don't.

"Their credibility has grown because they are seen as passionate, knowledgeable, and often deeply embedded in the communities they report on."

Queensland University of Technology

Queensland University of Technology

Weather influencers are part of the "attention economy" says Daniel Angus

Yet the issue with weather influencers, Prof Angus notes, is their tendency to scaremonger, as social media weather forecaster Higgins Storm Chasing, also based in Townsville, has been criticised for.

In 2018, it was criticised for predicting historic levels of rainfall and flooding to its one million Facebook followers, which didn't materialise.

Higgins Storm Chasing, which has hired professional meteorologist and amateur tornado chaser Thomas Hinterdorfer, didn't respond to the BBC's request for an interview.

"Weather influencers are often prone to hyperbolic and exaggerated claims, as they are not held to the same standards or consequences as their mainstream and official government counterparts, which has led to claims of scaremongering, and propagation of misinformation," explains Prof Angus.

"What we have to understand is that they are part of an attention economy. The more eyes they have, the more engagement they see on their metrics. The bureau and governments are very reserved in putting out alerts and evacuation orders, because it only takes a few non-events for people to lose their trust in them," says Professor Angus.

"They have to answer for that, whereas for Higgins or any of the others, there's ultimately zero accountability if they completely mess it up. "

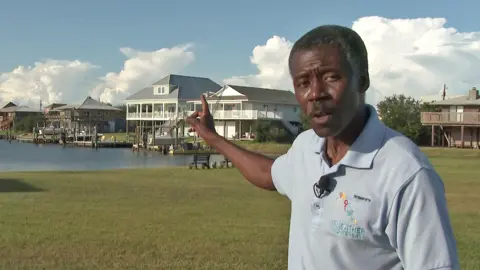

Alan Sealls

Alan Sealls

Alan Sealls warns against the accuracy of long-range weather forecasts

It's a view shared by Alan Sealls, a former TV weatherman who now teaches meteorology at the University of South Alabama, and consults as a forensic meteorologist, providing weather analysis for legal cases.

Prof Sealls is also now the president elect of the American Meteorological Society (AMS), which welcomes both professionally-trained meteorologists and weather influencers as members, so doesn't have an official position on the topic.

But Prof Sealls' personal view is that trained meteorologists with an online platform add value, while those without formal training stand to discredit the profession.

"There are those who are not formally-trained and take more risks in showing and promoting long-range weather outlooks, as though they are as accurate as short-range forecasts, particularly when the outlook hints at extreme weather. That's considered hype that makes people click and share, increasing the popularity of the influencer," he says.

"Trained meteorologists avoid that because it causes confusion in implying something distant is likely, when in reality it is uncertain and unknown.

"On the other hand, there are weather influencers who have the equipment and expertise to track and forecast local weather when it is extreme, in times of crisis, often giving more focus to communities that don't get full coverage from traditional TV stations. "

While Andrew Brown of Wally's Weather is self taught in meteorology, he has a masters in IT and numerous other technology qualifications.

His investment in forecasting equipment has been so big that he introduced paid subscriptions three years ago, but they mainly just cover his costs.

The advancement of AI, he says, gives him more time to accurately analyse data and communicate it to his followers. It will also allow him to expand to an Australia-wide operation.

Yet there is money to be made in the world of weather influencing. Colorado-based Andrew Markowitz has a meteorology degree and works full-time for an energy company, but also has 135,000 followers on a TikTok weather page.

Through a combination of live stream donations, sponsorships, brand deals, and TikTok's Creativity Program which helps creators monetise their content, Mr Markowitz says he can earn up to thousands of dollars a month.

"It's definitely not enough to quit my job, nor would I want to. I just treat it as fun money on the side, which I usually spend on travels," says Mr Markowitz.

Back in Australia, Mr Brown says he would like to retire from teaching, and have more time to focus on Wally's Weather, and to spend with his grandchildren, but acknowledges that this is a while away. But what he doesn't want is to be the face of the page - something he's so far avoided.

"I don't go out of my way to reveal who I am, because I like to be able to walk down the street and not be harassed. I've been interviewed on the radio before, and then walked past the person, and they had no idea it was me," says Mr Brown.

"Sometimes I can stand in line and hear people talking about the page, and they have no idea that I'm right there. It all adds to the fun."

More Technology of Business

10 hours ago

5

10 hours ago

5

English (US) ·

English (US) ·