ARTICLE AD BOX

Cecilia Barria

BBC News Mundo

Instagram/Andry Hernández

Instagram/Andry Hernández

Venezuelan Andry Hernández was awaiting a response to his asylum application in the US when he was deported to El Salvador

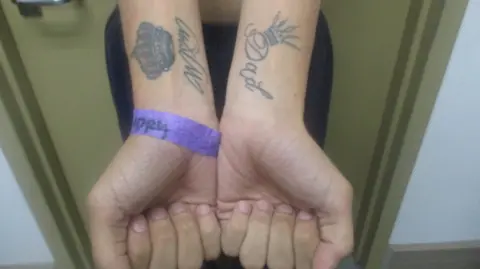

When Andry Hernández got a pair of tattoos on his wrists with the words mom and dad, he thought they would look even more striking if he added something else to them, according to the tattoo artist, José Manuel Mora.

"What if you add some small crowns?" Mr Hernández is said to have asked the artist.

The crown is the symbol of the Catholic annual Three Kings Day celebrations for which Mr Hernández's Venezuelan hometown, Capacho Nuevo, is famed.

Seven years later, those crowns may have led to Mr Hernández being locked up in El Salvador's mega-prison. He and dozens of other Venezuelans alleged by US President Donald Trump to be members of the Tren de Aragua gang were deported to the Central American nation in March.

"If I had known that the crowns would take Andry to jail, I would never have tattooed them on his body", Mr Mora tells BBC Mundo.

Mr Hernández left his hometown in Venezuela for the United States in May last year. Like many migrants, he began a long trip through the Darién jungle on the border between Colombia and Panama, on his journey to Mexico.

According to court documents filed by his lawyers, obtained by BBC Mundo, the 31-year-old surrendered at the border, at the San Ysidro Port of Entry, on 29 August after making an appointment with the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agency for asylum.

His asylum request claimed that he was a victim of persecution in Venezuela for his political beliefs and sexual orientation.

Court document

Court document

Mr Hernández has two crowns tattooed on his wrists along with the words "mom" and "dad" written in English

He was then taken into custody by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice), an agency within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and was sent to the Otay Mesa Detention Centre in San Diego.

At the centre, "he was flagged as a security risk for the sole reason of his tattoos", his lawyer wrote in a statement.

His legal team says Mr Hernández's interrogation at the centre was carried out by an official from the private company CoreCivic - a company contracted by the government - not by Ice agents.

CoreCivic official Arturo Torres, acting as interviewer, used a score system to determine whether a detainee is part of a criminal organisation.

It has nine categories, each with its own score. According to the criteria, the detainees are considered gang members if they score 10 or more points, and they are considered suspects if they score nine or fewer points.

Mr Hernández was given five points for the tattoos on his wrists, which included two crowns, according to paperwork signed in December 2024 by officers from the company.

The interviewing officer wrote: "Detainee Hernández has a crown on each one of his wrist. The crown has been found to be an identifier for a Tren de Aragua gang member".

The BBC has contacted CoreCivic for comment, but has not received a reply.

"So far, that form is the only government document linking Mr Hernández to the Tren de Aragua," Lindsay Toczylowski, executive director of the Immigrant Defenders Law Centre and part of the legal team representing the young Venezuelan, told BBC Mundo.

Authorities have not provided further information about Mr Hernández's case, or the charges faced by him or other Venezuelans recently deported to El Salvador.

Scorecards for 'alien enemies'

Lawyers defending migrants' cases do not know whether the particular score system that marked Mr Hernández as a suspected member of Tren de Aragua has been used during the assessment of other detainees. However, authorities have acknowledged that tattoos are one of the criteria used for identifying gang members.

According to court documents filed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) on behalf of Venezuelan deportees, there is second scoring guide which evaluates detainees on a 20-point scale.

The form instructs agents on how to validate detainees as a member of Tren de Aragua under the Alien Enemies Act - a centuries-old law that has been invoked by Trump to detain and deport individuals considered enemies of the United States.

Higher scores of 10 points are given to detainees who have criminal or civil convictions, sentencing memorandums, or criminal complaints that identify them as members of Tren de Aragua.

Lower scores are for those with tattoos denoting their membership or loyalty to the gang (four points) - or who have insignias, logos, notes, drawings, or clothing indicating loyalty to it (also four points).

The lowest scores (two points) are assigned if the detainee, for instance, appears on social media displaying symbols or hand gestures related to the gang.

BBC Mundo reached out to DHS and Ice to request information about the scoring system used in the two forms, but received no response.

However, DHS has previously published a statement on its website, called 100 Days of Fighting Fake News, stating that its assessments go well beyond tattoos and social media.

"We are confident in our law enforcement's intelligence, and we aren't going to share intelligence reports", the document said. "We have a stringent law enforcement assessment in place that abides by due process under the US Constitution."

Getty Images

Getty Images

More than 200 Venezuelan migrants were deported to El Salvador's mega-prison on 15 March

Jason Stevens, special agent in charge of the El Paso Homeland Security Investigations Office, told BBC Mundo that according to the guidelines, officers used a variety of criteria to identify a gang member.

He said in addition to an individual's tattoos, officers look at criminal associations, monikers, social media activity and messages on phones.

Lawyers representing deportees have included official government guidelines in their court cases, arguing that it is insufficient to identify a detainee as a member of Tren de Aragua based on photographs of tattoos.

Venezuelan researcher and journalist Ronna Rísquez, author of a book about Tren de Aragua, dismisses the idea that tattoos are a criterion that defines membership in this group.

"Equating the Tren de Aragua gang with Central American gangs in terms of tattoos is a mistake," she warned. "You don't have to have a tattoo to be a member of the Tren de Aragua gang."

Transfer to notorious mega-prison

Unaware that he was suspected of belonging to Tren de Aragua, Mr Hernández was expecting to appear in a US court for another asylum-related hearing that he hoped could eventually allow him to remain in the country.

By March 2025, he had spent nearly six months at the San Diego detention centre before being abruptly transferred to the Webb County Detention Centre in Laredo, Texas, while his asylum case was still pending.

He was not the only person who would be transferred to that second centre.

On 15 March, Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act to deport suspected Tren de Aragua members, arguing that Venezuelan authorities had ceded control over their territories to transnational criminal organisations.

Without being able to contest the charges, Mr Hernández was deported that day as part of a group of 238 Venezuelans and 23 Salvadorans, to El Salvador's notorious mega-prison, known as the Terrorist Confinement Centre (Cecot).

Mr Hernández had a court date scheduled for his asylum request, but according to his lawyers, authorities at the Webb County Detention Centre would not allow him to attend via video call.

Since then, no-one has heard from him. His parents had no information about him until they were told that someone had seen a photo of their son in a Salvadoran prison.

'Crown tattoos were Andry's crime'

Mr Hernández designed and hand-embroidered his own costumes for the annual religious festival of known as the Three Wise Men of Capacho, his family say.

He also designed the outfits for some of the girls for their own celebrations of the festival in his home state of Táchira, near the border with Colombia.

The symbol that identifies the religious festival - which was officially declared part of Venezuela's national cultural heritage, and of which its residents are proud - is a golden crown.

Since he was 7 years old, Mr Hernández has participated in the festival representing various biblical characters.

"Andry is a makeup artist, a theatre actor, and we all love him very much", said Miguel Chacón, president of the Capacho Three Kings Foundation, which organises the 108-year-old event.

"Some young people get tattoos of the kings' crowns like Andry did. That was his crime."

Hundreds of people in Capacho Nuevo, a modest agricultural town, participated in a vigil at the end of March to demand Mr Hernández's release. Some of them wore crowns.

One of Mr Hernández's friends, Reina Cárdenas, maintained contact with him until a few days before his deportation. She showed BBC Mundo official documents indicating that the young man had no criminal record in Venezuela.

Instagram/Andry Hernández

Instagram/Andry Hernández

Mr Hernández has participated in the Capacho Three Wise Men festival for over 20 years; its symbol is a crown

Mr Hernández dreamed of opening a beauty salon and helping his parents financially, Ms Cárdenas said by phone from Capacho Nuevo.

Seeking a better future, Mr Hernández left his hometown and lived in Bogotá for a year, where he worked as a makeup artist and as a hotel receptionist.

He returned to Venezuela after receiving a job offer at a television channel in Caracas, where he was excited by the idea of doing makeup for presenters, models, and beauty queens, Ms Cárdenas said.

"He did not stay in the TV station for more than a year because he was discriminated against for his sexual orientation and because of his political beliefs," she noted. "He received threats."

Mr Hernández decided to leave Caracas and return to his hometown. "He wasn't well, he didn't want to leave his house," his friend said. He remained there for five months until May 2024, when he decided to travel to the US through the Darién jungle, despite his mother urging him to stay.

Family handout

Family handout

Members of Mr Hernández's family - joined by costumed attendees of a vigil - have called for his release

Today, Mr Hernández's mother, Alexis Romero de Hernández, can hardly bear the pain of not having him by her side.

"I'm waiting for news of my son," she told BBC Mundo. "I want to know how he is. I wonder how they're treating him. If they gave him water. If they gave him food. Every day I think about him and ask God to bring him back to me."

The last known image of Hernandez is a photo taken of him on the night of 15 March inside the Salvadoran mega-prison, when a American photojournalist Philip Holsinger documented the arrival of a group of alleged criminals for Time magazine.

That was when he took a photo of a young man saying "I'm not a gang member. I'm gay. I'm a barber", Mr Holsinger wrote in his article.

The man was chained and on his knees while the guards shaved his head. Mr Holsinger later learned that man was Mr Hernández.

"He was being slapped every time he would speak up… he started praying and calling out, literally crying for his mother," Holsinger told CBS. "Then he buried his face in his chained hands and cried as he was slapped again."

Mr Hernández's case has caused a stir in the US, and mystery surrounds his whereabouts.

California Governor Gavin Newsom has requested his return, while four US congressional representatives travelled to El Salvador and requested to be provided with proof of life for him. They did not get it.

6 hours ago

4

6 hours ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·